As had happened 25 years previously, the outbreak of the Second World War brought a halt to the Football League and FA Cup competitions.

Both tournaments were cancelled early in the 1939/40 season, with West Ham United’s Second Division campaign ended at the start of September, just three games in.

Six weeks later, a regional competition began, with the Hammers in League South alongside nine other London and South Coast clubs.

With uncertainty due to the escalation of hostilities and many players unavailable, the season was split into two parts.

The Irons did well in both, finishing second in League A, which ended in February 1940, and League C, which ran until June 1940.

A knockout competition was also held, the Football League War Cup, and again Charlie Paynter’s squad showed up positively, defeating Chelsea, Leicester City, Huddersfield Town and Birmingham to set up a semi-final with Fulham.

A thrilling 4-3 win saw the Hammers reach the final, where they would face Blackburn Rovers at Wembley Stadium on 8 June 1940.

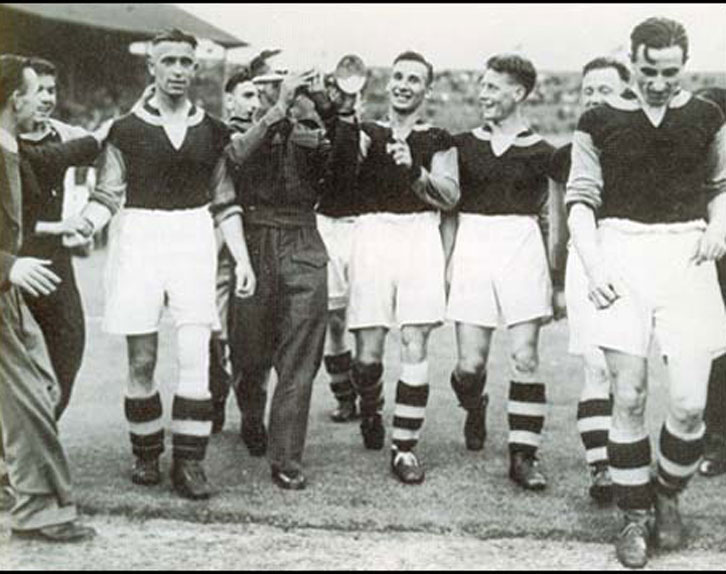

There, in front of 42,399 brave supporters, who braved the threat of a Nazi air raid, Sam Small scored the only goal of the game to secure a welcome piece of silverware and boost the morale of east Londoners who had already been targeted by the Luftwaffe.

It was an historic moment for the Hammers, who won at what had become the national stadium for the first time and collected their first piece of silverware since lifting the London Challenge Cup a decade before.

Those bombing raids would increase hugely in September of the same year, when the eight-month long Blitz began.

As had occurred during the First World War, West Ham players had signed-up to join the war effort.

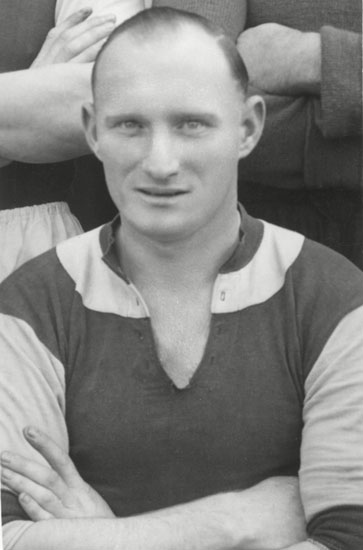

Among those who did so was Scottish goalkeeper Norman Corbett, who had made his first-team debut in a Second Division win over Sheffield United in May 1937 and totalled 42 appearances before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Corbett joined the Essex Regiment and was serving during West Ham’s run to the War Cup final. He was given leave to feature in ties against Chelsea and Leicester City, but arrived midway through the final, before celebrating on the pitch with his jubilant teammates, in uniform, after the final whistle.

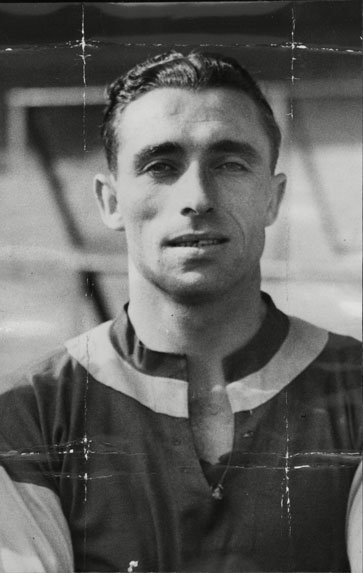

Among those Corbett celebrated with was Archie Macaulay, a fellow Scot who also joined the Essex Regiment, combining his Army duties with playing for the Hammers.

A future Scotland international Macaulay had scored 28 goals in the two seasons before war broke out and continued to play intermittently throughout the conflict.

Both featured during the 1940/41 season, which proved to be another successful one, with the Hammers winning 14 of their 25 War League South matches.

The structure of the league competition was changed in 1941/42, when a 16-team London League was introduced, albeit one that included Portsmouth, Aldershot, Reading and Brighton. Again, Paynter’s side excelled, finishing third behind Arsenal and Portsmouth.

The Irons’ fine form in those first three seasons held during the War was based on the goalscoring of their two outstanding forwards, Alex George Foreman and Joseph Stanley Foxall, who combined to net an amazing 154 goals.

The pair added 38 more – Foreman 30 of them – in 1942/43 as the Hammers finished sixth.

And Foreman bagged another 24 as the resurgent Irons won 17 out of 30 games to finish as runners-up to Tottenham Hotspur in 1943/44.

He had help, too, in the shape of long-serving inside-left and England international Len Goulden, who was into his thirties but still producing the goods on a regular basis. In all, he scored 52 goals in 152 war-time appearances for the Club he had originally joined as long ago as 1932, while also featuring for England in six unofficial war-time internationals.

Seventeen of those 152 goals came in the final season of war-time football, 1944/45, when the Hammers won 22 of their 30 London League matches, but still finished as runners-up to Spurs for a second straight season.

West Ham’s fine 1944/45 campaign was all the more impressive when you consider the team played their first 14 fixtures away from home after the Boleyn Ground was hit by a German V-1 flying bomb in August 1944.

The bomb landed on the south-west corner of the pitch, causing major damage and a fire that destroyed the offices and a number of important records and archives.

The Irons lost just three of those 14 matches, recording nine wins in a row between 16 September and 11 November.

After returning home in December 1944, West Ham thrashed Aldershot 8-1 and Luton Town 9-1 and ended the season with 96 goals scored in their 30 matches, but still finished five points behind a Tottenham team who lost just one game all season.

Mercifully, the 1945/46 season proved to be the final one of war-time football, as the conflict came to an end in September 1945.

West Ham signed-off the regional competition by finishing seventh in a 22-team South League, which included teams as far afield as Wolverhampton Wanderers and Plymouth Argyle.

The post-War years are seldom talked about when discussing West Ham United’s history but, in some ways, they were a pivotal period.

The Football League was reintroduced for the 1946/47 season, ending seven years of regional competition, with the Hammers in the Second Division.

As was so often the case throughout the Club’s 125-year history, West Ham relied on their home form to collect the majority of their points, registering 12 of their 16 league wins at the Boleyn Ground, while their away performances often left something to be desired. A haul of 40 points saw Charlie Paynter’s squad finish 12th of 22.

Perhaps the most pleasing aspect of the campaign was the amazing goalscoring form of Frank Neary, who finished as the Irons’ leading marksman with 15, despite playing just 14 league games.

A former Army PT instructor signed from Queens Park Rangers for £4,000 in January 1947, Aldershot-born Neary made an electric start to his career in Claret and Blue, scoring twice in 3-0 home wins over Newport County and Swansea Town before hitting a hat-trick against West Bromwich Albion on 15 March 1947.

However, after playing three times at the start of the following season, during which he failed to score, Neary departed for Division Three South club Leyton Orient for a fee of just £2,000.

Rumours abounded of the reasons for his sudden exit, with one story that emerged following his death suggesting the forward had been allowed to leave after an on-field altercation with an opponent was spotted by Chairman WJ Cearns.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Neary continued to score regularly for Orient, QPR, Millwall and non-league Gravesend before hanging up his boots in 1954.

With Neary gone, West Ham failed to score enough goals to seriously threaten a return to the top-flight in 1947/48, with Eric Parsons topping the charts with just eleven.

Even so, an improved defensive showing saw the Hammers enjoy their best season in some time, finishing sixth, albeit 13 points behind champions Birmingham City and ten adrift of Newcastle United in the second promotion place.

Despite a strong finish to the season that saw the Irons win two of their final three matches, manager Paynter’s long association with West Ham was coming to an end.

With the Hammers failing to mount sustained challenges for promotion to the First Division, and Paynter approaching his 70th birthday, the Club’s hierarchy began to think about transitioning to a new strategy.

In 1948, former player Ted Fenton was brought back to the Boleyn Ground as Paynter’s assistant, having served an apprenticeship as manager of Southern League side Colchester United.

Born in Forest Gate, Fenton had played 166 Second Division games before the Second World War, then continued as a guest player while serving as a PT instructor in the Army during the conflict, appearing in the 1940 War Cup final win over Blackburn Rovers at Wembley.

Now in his mid-30s, Fenton’s bright mind and willingness to embrace change and innovation made him the ideal man to replace the older Paynter.

It would take some time for Fenton’s ideas to have an impact, though, and West Ham again finished ten points behind the promotion places in 1948/49, this time in seventh place.

For the second season in a row, the lack of a prolific goalscorer was the main issue, with only Ken Wright (eleven) and Bill Robinson (ten) reaching double figures.

The 1949/50 season proved to be Paynter’s last as manager and also to be one of the worst in West Ham’s 125-year history, at least in terms of league position.

Despite Robinson’s 23 goals, the Irons won just 12 of their 42 Second Division fixtures, collecting just 36 points and finishing in 19th place, just four points and two places above relegated Plymouth Argyle.

After 18 years, 480 matches and 198 victories as manager, aged 70, Charlie Paynter’s long spell as West Ham’s second full-time manager was at an end.

Now in charge, Fenton set about overhauling the playing squad, introducing young, hungry players who he hoped would set the Club on the right track for years to come.

Among those who debuted in 1950/51 were centre-half Malcolm Allison, Irish wing-half Frank O’Farrell and winger Harry Hooper, all of whom would play their part in West Ham’s 1950s renaissance and, individually, go on to achieve great things in the game.

They were joined in the team by others who had debuted the previous season, including Robinson, who would later join the coaching staff and oversee the youth team, developing the likes of Bobby Moore and Geoff Hurst.

With a relative lack of finances available to buy experienced players, the seeds were being sown for the creation of a system that would see West Ham scout, recruit and train the best young players they could find – a system that would become known as ‘The Academy of Football’.