Veteran Evening Standard reporter Ken Dyer reflects on more than 60 years as a West Ham United supporter by telling the stories of Bobby Moore and Wolverhampton Wanderers legend Billy Wright...

Statues have been in the news recently but as I look forward to Sunday’s West Ham v Wolves match I can immediately think of three which are, without question, an eternal source of pride for supporters of both clubs.

Back on the corner of the Barking Road and Green Street, you can see Bobby Moore, the Jules Rimet Trophy in one hand, being lofted high by his England colleagues Sir Geoff Hurst and Ray Wilson, while the third member of the Hammers’ World Cup winning triumvirate, the late, great Martin Peters, looks on.

At Wembley, the scene of that ‘66 World Cup triumph, standing 20 feet tall on a stone plinth, a bronze statue of Bobby looks out over supporters as they make their way up Olympic Way.

A fourth statue, of Bobby Moore, Sir Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters, is also planned for Champions Place, at London Stadium, as part of West Ham’s 125th anniversary celebrations this year.

Such statues are the ultimate recognition of the level of influence the subjects have had on people during their lives.

Bobby Moore and Billy Wright were great captains of both club and country. Billy won 105 caps for his country, a record which Bobby eventually beat by three.

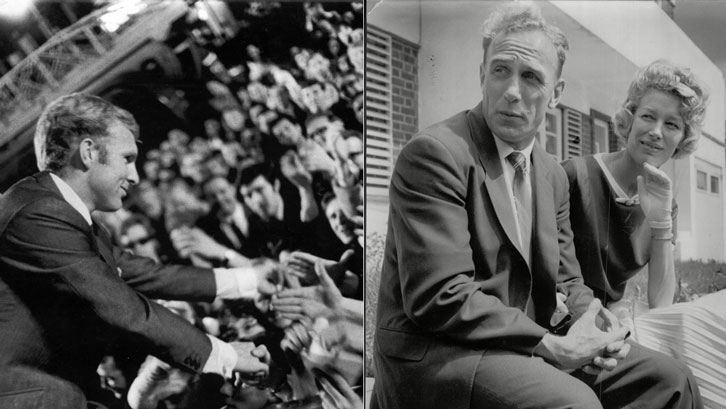

The two men also had ‘celebrity’ status long before it became commonplace.

Billy Wright, once considered ‘too small’ to become a footballer, married Bethnal Green-born Joy Beverley who, with her twin sisters, became a top popular music singing group of the 1950s and ‘60s.

Bobby, meanwhile, was the epitome of class and coolness, throughout his stellar playing career. After his retirement in 1959, Billy managed Arsenal for four years between 1962-66 and subsequently became Head of Sport for ATV and Central Television. In 1990 he became a Wolves director.

As a player he was, in some ways, similar to Bobby Moore. They both played at the back and what the Wolves star lacked in pace, he more than made up for with his reading of the game. Both men had that knack of staying cool even in the heat of battle and Wright was never booked or sent-off in his playing career.

Billy Wright died, of cancer, in 1994, aged 70, less than a year after the disease had claimed West Ham’s greatest player, aged just 51.

Even then, though, these two great old clubs were connected since West Ham’s next home game, following Bobby Moore’s death, came on 6 March 1993 – against Wolves.

Sad and poignant as it was, that day is another of my outstanding memories of a lifetime, first supporting and then covering West Ham United for the Evening Standard.

I can still vividly recall exactly where I was when the office called me to tell me my boyhood hero had passed away and a few days later, along with many thousands of others, I made my way, with my daughter, to Upton Park to pay my respects and wonder at the sheer volume of memorabilia surrounding the gates at the entrance.

I was up in the Press Box when Bobby’s two former England and West Ham colleagues, Sir Geoff Hurst and Martin Peters, carried a floral replica of his number six shirt to the centre circle before the game, accompanied by Ron Greenwood.

A number of Bobby’s former team-mates were also there that day and when the eyes were dry again, the football took centre stage, which was what Bobby would have wanted.

Another of Wolves’ icons, striker Steve Bull, opened the scoring in the 57th minute but inside 60 seconds, Mark Robson crossed from the left and Trevor Morley headed an equaliser.

Kevin Keen was floored for a penalty which Julian Dicks duly thumped home for number two before substitute Matty Holmes made sure of a home victory when he netted a third before the end.

Both men won the Football Writers’ Association Footballer of the Year award, Billy in 1952 and Bobby 12 years later.

The pair carried their ‘celebrity’ status with quiet dignity, even when they were subjects of TV’s This Is Your Life.

As captains of both their clubs and country, they led by example, as Wright explained in an interview.

“I decided early on that the art of captaincy is leadership, not dictatorship,” he said. “Respect is the hardest thing for a captain to come by and the easiest to lose. I never changed my mind about this.”

The thousands who have stood and admired the statues of these two exceptional men, at Wembley, the Barking Road or Molineux, would agree with that.