The second part of a new series, we continue our alphabetic journey through 125 years of West Ham United history…

Boleyn Ground…

West Ham United moved to the stadium known as the Boleyn Ground for the start of the 1904/05 season.

The actual stadium was built on a plot of land next to and in the grounds of Green Street House. The field in which the pitch was to be laid was originally used to grow potatoes and cabbages and, as such, the pitch was often referred to by the locals as 'The Potato Field' or 'The Cabbage Patch', while the ground itself was originally named ‘The Castle’ during its initial 1904/05 season.

Initially leased from the Roman Catholic Ecclesiastical Authorities – but not before a lengthy debate that saw manager Syd King visit his friend, the influential MP Sir Ernest Gray – the Hammers' new home originally consisted of a small West Stand and covered terrace backing onto Priory Road, along with dressing rooms situated in the north west corner between the West Stand and North Bank.

West Ham's first game at their new home was against Millwall on 1 September 1904. It drew a crowd of 10,000, the majority of whom were rewarded as West Ham ran out 3-0 winners.

The ground was developed and improved over the following decades. However, in August 1944 much of that good work was ruined when a German V-1 flying bomb landed on the south-west corner of the pitch. The bomb not only caused severe damage to the ground, but the resulting fire also gutted the Club's offices and destroyed historical records and documents.

West Ham were forced to play ten war-time matches away from home while repairs were carried out, return in December 1944.

In January 1969, the new East Stand replaced the famous 'Chicken Run' terrace - an area of the ground where fans were stood very close to the pitch, allowing them to make life very uncomfortable for opposition wingers!

The following year, on 17 October 1970, a record league attendance of 42,322 turned out to watch the Hammers draw 2-2 with rivals Tottenham Hotspur in Division One.

The Boleyn Ground underwent extensive redevelopment work in the early 1990s in the advent of the Taylor Report. In 1993, a new South Stand was opened and named in honour of Club legend Bobby Moore. The Bobby Moore Stand is home to the Club offices.

Two years later, the North Bank was replaced by a 6,000-seat stand initially named the Centenary Stand for obvious reasons, but subsequently re-named in honour of Sir Trevor Brooking in 2009.

The last and largest of the Boleyn Ground stands to be replaced was the West Stand, which was rebuilt as a 15,000-seat structure and opened by HM The Queen in 2001. The new West Stand contains a hotel, executive boxes and other facilities.

West Ham vacated the Boleyn Ground after 112 years in the summer of 2016, defeating Manchester United 3-2 in a thrilling final game.

Browning Road...

When Thames Ironworks FC were evicted from their first home at Hermit Road in late 1896, the Club’s owners had to find them a suitable ground to complete their inaugural London League season.

After playing five matches away from home between October 1896 and March 1897, Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company managing director and Club Chairman Arnold Hills leased a temporary home at Browning Road, a couple of miles away in East Ham.

Thames Ironworks' first match at their new home came on 6 March 1897, when the hosts scored a 3-2 London League win over Ilford. A crowd of 1,500 spectators turned out to see Charles Read score twice and Butterworth once to secure a winning start.

However, the new situation was not ideal, as explained by future Ironworks player and West Ham United manager Syd King in his 1906-published ‘Book of Football’.

“For some reason, not altogether explained, the local public at this place did not take kindly to them and the records show that Browning Road was a wilderness both in the manner of luck and support," wrote King.

With the Club's presence never likely to be permanent, Hills earmarked a large piece of land in Canning Town and would eventually spend £20,000 on the construction of the huge Memorial Grounds.

On 8 April 1897 came not only Thames Ironworks' final game of the 1896/97 London League season but their last fixture at Browning Road. The match against Barking Woodville ended 1-1, with the hosts’ goal being scored by Scot Andrew Cowie on his own final appearance for the Club.

Perhaps more telling was the attendance, just 600, which was an example of the struggle the Club had in attracting attendances to Browning Road.

Despite the uncertain situation surrounding their home stadium, Ironworks won seven of their 12 league matches to finish second in the table behind champions 3rd Grenadier Guards.

Bubbles…

In the mid-1920s, it was adopted by West Ham United supporters, who had doubtless heard it, but the circumstances around its arrival at the Boleyn Ground remain shrouded in mystery.

One theory goes that schoolboy football was hugely popular at the time, drawing hundreds of supporters to matches across the County Boroughs of East and West Ham on Saturday mornings.

One of the standout teams hailed from Park School, whose headmaster Cornelius ‘Corney’ Beal was a big football fan and a friend of West Ham United trainer and future manager Charlie Paynter.

Beal also had a talent for music and rhymes and wrote special words to the tune of Bubbles and when a Park School player was having a good game the spectators would mention him by name in a parody of the tune.

One such player was W. (Billy) J. ‘Bubbles’ Murray, so called because of his distinct and almost uncanny resemblance to the boy in the famous painting by Millais entitled ‘Bubbles’.

The schoolboy was a talented right-half who, alongside future Hammers great Jim Barrett, was part of the West Ham Boys side which often played at the Boleyn Ground, meaning Beal’s ditties were often heard in Upton Park in his honour.

A second theory is simply that Bubbles was such a popular tune that it was simply played by the succession of bands who provided musical entertainment before kick-off and at half-time, including the Beckton Gas Works Company Band, Metropolitan Police Band, Leyton Silver Band and British Legion Band.

And a third is that Swansea Town fans sang Bubbles at an FA Cup tie at the Boleyn Ground in 1921 and the home supporters took the song for their own.

Whatever the truth, the tune is synonymous with West Ham United and, a century after it was first sung, it is heard whenever and wherever the Hammers are in action.

Brothers…

The first siblings to pull on the shirt were the Bromley-by-Bow born Hilsdons. Prolific striker George – nicknamed ‘Gatling Gun’ (pictured, left) for his shooting ability – netted 35 goals in 96 appearances in two spells between 1904-06 and 1912-14. In between, George scored 14 goals in eight games for England and more than 100 times for Chelsea. His older brother Jack played just once for West Ham, in September 1903.

The Denyers also featured in the years before World War One. Plaistow-born forward Bertie scored 16 goals in 46 appearances, while defender Frank featured just twice, with the appearances coming on consecutive days in April 1911.

Three decades later, three Corbett brothers pulled on the Claret and Blue shirt.

The most famous was right-half Norman, who was a member of West Ham’s Football League War Cup-winning squad, but missed the final at Wembley as he was travelling back from Army duty with the Essex Regiment. Signed from Edinburgh club Heart of Midlothian, the Scot totalled 306 appearances between 1937-50, scoring eight goals.

Norman’s older brother David had earlier joined from Dundee United and played four games in 1936/37, before joining Southport, while centre-half Willie guested for the Irons during the Second World War before going on to make 60 senior appearances for Celtic.

The late 1930s also saw the Fentons become the first and only brothers to play in the same West Ham first team.

Older brother Ted (pictured, below) played 146 times between 1937-46 and lined up alongside his younger sibling Benny on four occasions, before famously going on to manage the Irons to the Second Division title in 1958.

Ted was also an architect of the Academy of Football, establishing a youth development structure that saw the Hammers reach two FA Youth Cup finals and recruit many of the players who won trophies with Club and country in the 1960s.

Less famous were the Nelsons, Bill and Andy, who were born in Custom House and made two and 23 appearances respectively during the 1950s.

Canning Town-born John and Clive Charles graduated from Ted Fenton’s Academy and were the first black players to appear for West Ham in the Football League.

A tenacious full-back, John captained the Hammers to FA Youth Cup glory in 1963, by which time he had already become the first black player to appear for England, scoring for the U18s in a 3-1 win over Israel in Tel Aviv in May 1962.

John went on to play 142 times between 1963-70, before Clive, seven years his junior, featured 15 times in the early 1970s.

It would be nearly 30 years before the sixth and most-recent set of brothers appeared – the Ferdinands.

Born in Peckham, south London, Rio joined the Academy at the age of 13 in 1992 before going on to win Hammer of the Year honours while still a teenager.

Ferdinand, of course, went on to captain England and win a succession of major trophies with Manchester United.

Younger brother and fellow Academy graduate Anton also enjoyed a productive West Ham career, winning promotion in 2005, starting the FA Cup final in 2006 and pulling off a Great Escape in 2007.

Brazil…

Among those to visit were Olaria of Brazil, who travelled from Rio de Janeiro to east London to take on the Hammers on the evening of Tuesday 27 April 1954. The game ended in a goalless draw.

Brazil won the FIFA World Cup in 1958 and, as a result, their club teams became popular guests.

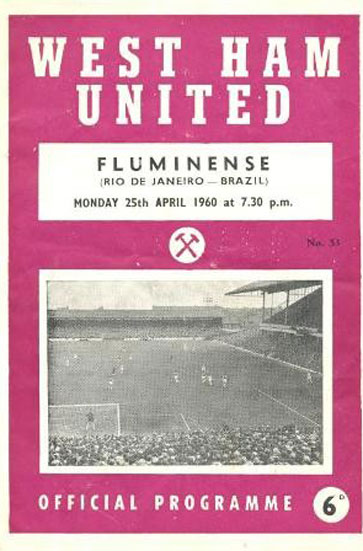

And so, in April 1960, Fluminense were invited to the Boleyn Ground and partook in a far more entertaining match, with West Ham running out 5-4 winners.

The 1960s also saw the growth of ‘soccer’ in the United States, with European clubs visiting America during the close-season and taking part in the International Soccer League.

The 1963 edition saw West Ham win the trophy, drawing 1-1 with Recife of Brazil on the way. Johnny Byrne scored the Irons’ goal in a game that was held in New York and kicked-off at midnight local time due to the high summer temperatures!

And Ron Greenwood’s men returned to New York in September 1970, when Bobby Moore and Pele resumed their monumental battle from that summer’s FIFA World Cup finals.

West Ham took on Santos at Randall’s Island, drawing 2-2, with Pele scoring both goals for the Brazilians, and Clyde Best replying with two for the Londoners.

In 1991, West Ham took on Botafogo in a pre-season match at the Boleyn Ground in August 1991, losing 2-1, with Trevor Morley scoring the hosts' goal.

Player-wise, West Ham have been represented by three Brazilians – forward Ilan, attacking midfielder Nenê and winger Felipe Anderson.