Matt Dickinson explains how It took the vision of Ron Greenwood to set West Ham and England’s finest player Bobby Moore on his way to football immortality...

Bob Dylan sang that the times were a’changing. English football was a’changing, too. Among all the great revolutions of the sixties, the decade of rock and roll and rockets to the moon, the arrival of the back four was not sexy or swinging but it has endured long after mop tops and psychedelic prints have gone out of fashion.

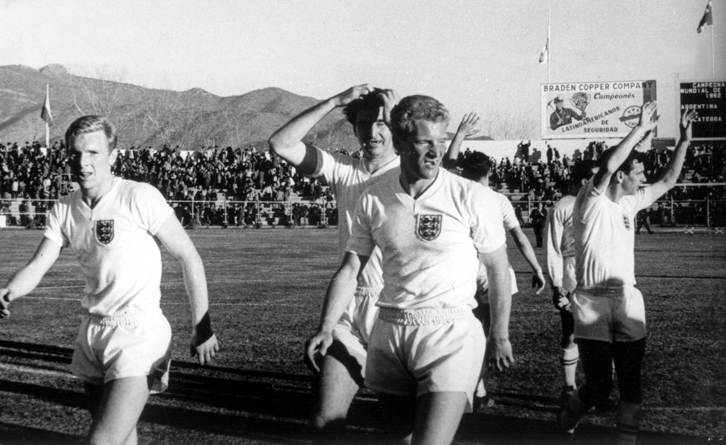

At the 1958 World Cup finals, Brazil had caused a stir and not just because of a teenage sensation called Pelé. With attacking full-backs and two centre-backs, the South Americans popularised a new 4-2-4 strategy. In England, Greenwood was one of the trendsetters, recognising the benefits of the back four – and, most importantly, how it could work perfectly for Bobby Moore.

Moore had moved around several positions. Greenwood had seen him in the junior England teams as a traditional centre-half. In the WM formation which English clubs had slavishly followed for decades, the position was essentially destructive. In the Soccer Syndrome, John Moynihan wrote that the stopper’s only task was to track the centre-forward ‘like a casino manager watching a con man’.

According to Brian Glanville, it had ‘become the Frankenstein’s monster of modern football’, the least demanding position on the field with no creative responsibility. There were skilful exceptions, but mostly it had been a role for tall bruisers, and Moore could be exposed there.

In West Ham’s youth team, some of his team-mates fretted when he faced quick centre-forwards or specialists in the air. They worried about Moore being isolated in that key position because of his lack of pace and reluctance to join the aerial battle. ‘Bobby didn’t particularly like heading the ball because it was untidy,’ says Ken Jones, who covered Moore’s career for the Daily Mirror. ‘Bobby wasn’t interested in untidy.’

In the first team, Moore had mostly been used as a destructive half-back, a midfield scuffler sent out to close down a particular opponent but one day in February 1962, Greenwood pulled Moore aside on the training ground ahead of a match against Leicester City. He explained that he was withdrawing him into defence: ‘I want you to drop back, to play deeper and play loose.’ He was playing him as a ‘spare’ centre-half alongside Ken Brown, effectively making a back four.

They hardly sound like the words to change a career, and certainly not the course of English football. No one hailed the new role at the time, but Geoff Hurst is in no doubt about the deep and lasting significance of that tactical switch. ‘Perhaps Ron’s masterstroke,’ he says, which is quite an accolade considering that Hurst himself was transformed, in a brilliant piece of coaching alchemy, from a middling midfielder to a powerhouse centre-forward who would make an historic impact.

A masterstroke it was. Moore immediately thrived in his role off Brown, seeing problems and smothering them. As Brown battled with the centre-forward, Moore tidied up, bringing order to the defence the way he brought it to his sock drawer and his rack of shirts.

He was always more perceptive than most thanks to the lessons of Allison. Dropping back from the hustle and bustle of midfield allowed his awareness to flourish. It was the skill which, many years later, would prompt the great Scottish manager Jock Stein to say ‘there should be a law against Moore – he can see things 20 minutes before everyone else’.

With the game now laid out in front of him, Moore could use good judgement to help compensate for the lack of pace. His distaste for heading was no longer such an obvious drawback as he learned to drop off and, far more elegantly, take the ball on his chest.

As Moynihan put it, Moore was ‘a smooth, streamlined young Londoner with the appearance of a male model, whose methods have been built for the new emancipated soccer of 4-2-4 and 4-3-3’. The game was changing and Moore had all the qualities to adapt with it. ‘Moore had found his niche,’ Greenwood said, with pride and delight.

Ken Jones, for decades one of Fleet Street’s most perceptive readers of the game, believes that it is hard to overstate how the new tactics shaped Moore’s career: ‘I’m convinced that the change in the way the game was played helped to make Bobby Moore a truly great player.’ Without Greenwood Moore might not have been a world-class defender; he might not have been a defender at all.

This was not just about tactics boards. Great players redefine positions by their own unique, and unmistakeable, qualities. Plenty of English teams embraced the new era but it was Moore who showed just how in influential the new role could become.

He described himself as a ‘sweeper’ which, Greenwood noted proudly, ‘was not a position anyone had heard of before’. Yet the label does not quite fit. Typically, Moore was being too self-deprecating. He was not stationed behind a back line in the libero position that was becoming so common in Italy into the sixties, but just to the left of a stopping centre-back with the freedom to stride forward. ‘Sweeper’ does not begin to do justice to Moore’s range and influence; watching him build play from the back was like watching a team with rear- wheel drive.

He had the accuracy to do it. The sight of Moore striding into midfield and chipping the ball forward would become so commonplace that the players used to joke that Geoff Hurst must have a bull’s-eye on his chest, so frequently could Moore find the target. He played like a gridiron quarter-back, initiating moves with flighted, angled passes.

Allison had always encouraged him to play from deep, and Greenwood preached from the same gospel. When Moore’s ambition proved costly in one game, possession lost and a goal conceded as he tried to carry the ball out of defence, Greenwood told the press that he would much prefer to see a well-intentioned mistake of over-elaboration than a clearance hoofed into the stands.

To a twenty-first-century eye, Moore’s range of influence is startling. What central defender of the modern era would you see breaking forward so boldly, imposing a pattern on the game from centre-half? Modern football has its ball-playing defenders and those with adventurous spirit, but in a game with such aversion to risk, the surging centre-back is almost as extinct as the old five-man attacks. To wish for another Moore may be as romantic, and as pointless, as yearning for another Sinatra.

An extract from: ‘Bobby Moore: The Man in Full’ by Matt Dickinson, published by Yellow Jersey Press, priced £9.99